A flawed system, built with good intentions: A closer look into the vaccine rollout for teachers

Recent discoveries have unveiled the vaccine inequities between public and private school teachers.

As the world paused to accommodate the needs resulting from the COVID-19 virus, I was able to live through this experience with two educators during the transition into online learning. I think it’s rather uncommon to have not only a mom as a teacher but also a dad as a principal, which is why I feel inclined to share their stories. It’s difficult to watch their district board meetings, which is, I’m sure, similar to those in Palo Alto, where angry parents write emotional letters about why their kids must return to school without knowing or taking the time to understand the complexities that go on behind the scenes.

My parents became concerned upon learning that returning to in-person school would be prioritized, as neither of them was vaccinated – none of their coworkers were vaccinated. One comment my mom made kept me up that night: “Public school teachers are continuously overlooked; we’re underpaid, and we’re under-appreciated, what makes you certain we’ll be prioritized to receive a vaccine before we go back to work?”

This is a lot to unpack, so let’s start at the beginning. For context, my dad is a principal in the Jefferson Elementary School District, and my mom is a teacher in the San Mateo Union High School District. Even though they are both educators, working in fairly similar areas, their Covid protocols are vastly different. My mom has been teaching from home since March 2020, and her school has just returned to in-person learning as of late April 2021. On the other hand, my dad is considered an essential worker as a principal and has been going to work every day, where he provides Covid tests for faculty and staff, distributes Chromebooks to his students, and facilitates the much-anticipated return of his elementary school students.

Throughout the year, they’ve both attended many meetings with colleagues in their districts to discuss how they’re going to mitigate the effects of Covid on their students. Their meetings often centered on how equity must remain at the forefront of every decision when choosing who comes back to school, and how to ensure everyone receives an equal education – leaving no student behind. Additionally, these meetings consider how to enact safety protocols that will guarantee student safety during in-person learning, such as up-to-date air filtration, cohorts, and distanced desks.

We’re very lucky here at Castilleja to have access to small class sizes, weekly Covid tests, and vaccinated teachers. However, that was not the case for many public schools. My dad works in a district where not every family is afforded the benefit of health care, so not every student, parent, or teacher is or can be vaccinated. My mom works in a district that serves about 8,400 students, around 1,200 kids per school, so it’s not as easy to create space for socially distanced classrooms. Furthermore, when schools were pushing to return in the early Spring, the number of those vaccinated, especially teachers in their district, was not high enough to ensure their complete safety.

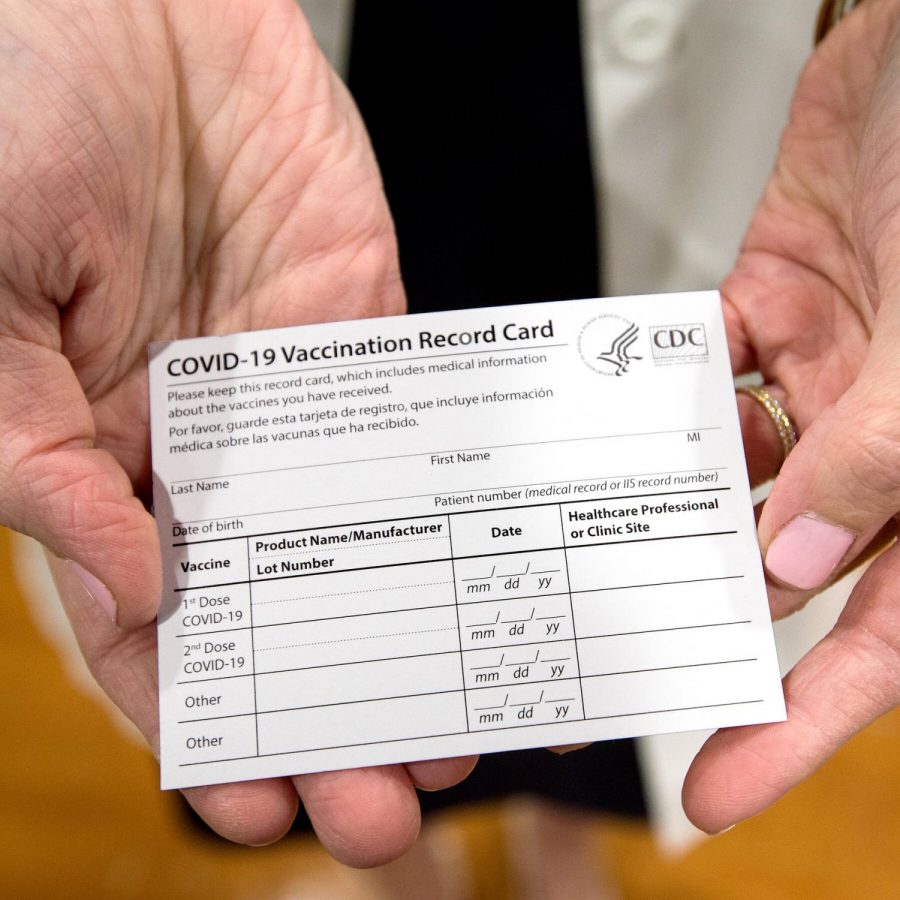

These statements might be confusing if you aren’t familiar with the nuances of the vaccine distributions for teachers, but with two parents hoping to get back on campus, this is the source of major discussion in our household. The concern amongst colleagues in my parents’ school districts rose: even though they were scheduled to return to campus in April and May, and my dad had been working in person for the entirety of quarantine, neither of them was eligible to receive a vaccine.

The issue is that certain educators are prioritized over other educators when it comes to vaccinations. California’s vaccine briefing for educators (released February 25th) states that “education workers will qualify for an expedited appointment based on whether they are or soon will be exposed to occupational COVID-19 risks. Specifically, workers will qualify if they are working in-person or will soon work in-person.” Essentially, the briefing declares that if your school has not returned to in-person learning, you are a lower priority to get vaccinated in comparison to teachers who have already returned to campus.

In hindsight, this makes sense, but as I looked at the ratio of private to public schools that have been able to return, many more private schools began in-person learning since they have the resources, funding, and smaller school population. So, when these guidelines came out, my already apprehensive parents became even more frustrated. To them, it further proved that private schools not only benefited from their ability to open earlier due to their size, but were now also prioritized to receive the vaccine first because they were able to open to in-person learning. They concluded that public schools need to receive the support that private schools are afforded.

Additionally, my dad works with a school with a high population of essential workers. Many families were at a greater risk of getting Covid, and many did. So, his school should have been a priority when the discussion about bringing kids back to school and getting their teachers vaccinated as soon as possible started – but they weren’t. Even though my dad was considered an essential worker and had been going into the office every day, because his school hadn’t opened to in-person learning, his school and staff were not a priority at the beginning of the vaccination rollout.

You can work for a school that has proven that its students are in need and that returning to school would provide so much good, but because you’re at a public school and haven’t been able to return, you’re no longer prioritized. It’s frustrating, as this just furthers the educational disparities because if these schools could bring their students back to school, the return to in-person learning would help get them back on track with the rest of the kids their age, as well as provide students who qualify with their one hot meal a day.

I talked to Don Scatena, Director of Student Services and CSM Middle College Principal, who confirmed that private schools (because of their smaller size), as well as charter schools, had an easier time returning to in-person learning. He described that these schools were able to get up and running faster, based on the criteria they had to meet: have the best filtration systems available, clear protocol, cohorts/bubbles of twelve, and their union’s sign-off. This proved difficult for the San Mateo public schools, as they have much larger class sizes that aren’t easily divisible by twelve, and the union wouldn’t approve their return. “Fear of the virus was a big deal for the union, we didn’t have a good testing or contact tracing protocol, as well as the staff needed for testing. So we didn’t actually start testing [staff] until late fall, November.”

These barriers further emphasize the work San Mateo Union is going to have to put in, as private schools in the area don’t have to answer to anyone, meanwhile the public schools had to wait some months more in order to get approved by the union to send limited students back to school in the late Spring. Mr. Scatena described to me what he hoped would be a robust summer program, in an effort to try and bring everyone back to speed. He noted that student enrollment was low, and so as of right now, he’s seeking to find a more long-term plan to increase instruction. Some developing plans include utilizing after-school hours, hiring more tutors, and revamping homework centers. He’s aware the instruction and level of understanding weren’t the same as they normally would be, so the district hopes to take advantage of the ELO grant from the state, which provides school districts with more money to implement smaller class sizes and more mental health therapists.

In addition to Mr. Scatena, I was also able to speak with Brittany Redgate, an English teacher at CSM’s Middle College, who provided an insightful and deeply personal account of the impacts COVID had on her life.

What were your thoughts on California’s vaccine briefing for educators that stated you were first qualified if you were working in-person, and your school had already returned?

I thought that was fair. It seemed like the vaccines should have gone to those who needed it most, and those who needed it most were those who were already exposed to the virus. I think, though, that this message came before I returned to in-person, so my school had not already returned (as indicated in your question).

Were you surprised by this – or on the contrary not at all, because public schools usually get the short end of the stick (as they hadn’t yet returned)?

No; unfortunately, I was not surprised by this. The lives of educators and under-resourced students had been undervalued in the national discourse around opening schools already (and historically in conversations surrounding public education). So, I was not surprised that these groups were being deprioritized to the voices and needs of the community that carried more political weight.

Were you ever willing to go back to school without being fully vaccinated, to aid the process in catching your kids up?

In my opinion, based on the formative data I was seeing, my students did not need to be caught up—they were in many circumstances doing quite well in mastering the skills of my course. This may have been because they are seniors in high school and had already built some critical community connections as well as key academic frameworks for accessing the material. Additionally, as a small program, we were able to assess socio-emotional needs with our students in a way that a larger school might not have been able to. For example, each teacher [at her program] met with 30-35 students every week to discuss any challenges they were facing to brainstorm solutions.

So, I’m not sure if I would have been willing to return without a vaccine. Fortunately, I didn’t have to make that choice, since I was fully vaccinated before we returned to in-person learning. In general, the idea of returning without a vaccine definitely stirred up fear, and it was a possibility that I definitely was not emotionally prepared for. I think this is because I got very, very sick in March of 2020, right after schools were shut down, and presumably with Covid (although there were not enough tests available at the time). As a result, I still suffer from long-hauler symptoms. Before I got sick, I was a healthy, active, 37-year-old athlete. I was running at least six miles a day; after getting sick, I wasn’t able to walk around the block without getting winded and needing an inhaler. This lasted for months, in addition to heart palpitations, body fatigue and a whole host of other issues. At one point, I had to take my partner (who is also a teacher and who also got sick) to the ER. When I dropped him off at the front door, because visitors were not allowed, it really hit me that I may never seen him again. It was the scariest experience of my life. So, although I felt relatively safe myself to return, because presumably I had the antibodies, I did not wish that experience on anybody else— especially students who felt pressured to go to school, putting them and their families at risk.

________________

The topic of the education gap is one that you might hear about a lot in the news, as the COVID-19 virus has only increased it, but what have our governors done to start closing the gap again? Education often takes a back seat, in comparison to big business and economics, but everyone understands the importance of it, so why don’t we value it as much as we should? Why not put the financial resources into the one U.S. system that actually impacts the future of this country? To put it simply, when we don’t prioritize vaccinating our public school teachers and principals, who have yet to return to school, we continue to undermine the value of a public school education.

As the vaccine rollout continues, while it’s important we celebrate a healthier and safer general public, it’s also important to recognize the inequities that many critical groups face when simply trying to get vaccinated. I’m hopeful that this article has provided some context for all that is on our teacher’s plates and the continuous hard work that goes on behind the scenes. Perhaps now as a society we can look at our teachers with more compassion and gratitude, and take a good look at what we value—maybe this time, we’ll invest in the quality of education for all kids, not just our own. For, in the words of Marian Wright Edelman, a good education is not meant to be a privilege amongst the wealthy, “education is for improving the lives of others and for leaving your community and world better than you found it.”

The March sequel to this article can be found here.

Loralei Rohrbach '24 is a staff writer for Counterpoint. In her free time, you'll always find her having a good time, cracking jokes, and chatting with...