Reckoning with reconciliation: Let’s learn from a “third world country”

Moira King and her sister, Claudine, posing in Rwanda on July 13, 2012

I remember the day quite vividly when someone mentioned that my new sister was from a third world country. I had been sitting at my first-grade table when the comment struck my heart in a way it hadn’t before. Pang. Claudine is from the country of Rwanda and moved in with us after coming to the United States for cancer treatment when I was six. I could not wrap my head around why someone would associate my role model with a somewhat negative term of her country, Rwanda.

It was only later when I was a little older that I started to really think about this classification. What was it about this term that angered me so much? Why did people automatically assume a lesser placement of a place so rich in culture and constant growth? And what did this say about America?

My sister, Claudine’s, parents died in the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide, a mass slaughtering of innocent civilians throughout the country between the months of April and July in 1994. The country had been divided between two groups. The groups were quickly pitted against each other. Very quickly hatred and fear grew to create one of the worst mass genocides in history. In just 100 days, almost 1 million people were brutally slaughtered. In just 100 days, neighbors became enemies. In just 100 days, the country was ruined by civil unrest and fear. A serious bloody wound left a serious scar on the country.

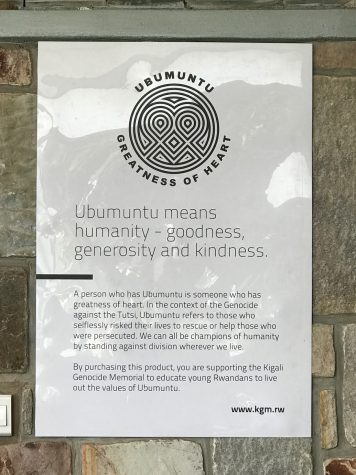

However, rather than sweeping its dark history under the rug, Rwanda chose to heal and acknowledge the genocide together. With implementations of new laws and infrastructure in the community and with empathy, Rwanda reconstructed itself into one of the most progressive countries in the world. First, they created the Gacaca courts, a nationally mandated court system in which those arrested for genocide-related crimes were tried in communities. Quite literally they would sit in front of and confess crimes to a victim’s family: “I killed your brother.” The community would then not forget, but acknowledge and forgive. Through this process, empathy was built into their new society. The leaders of Rwanda also implemented “Umuganda,” a community cleanup held on the last Saturday of every month. What is so striking about this idea is that the name, Umuganda, is a Kinyarwanda word that means “coming together in common purpose.” But this seemingly positive definition belies a dark legacy as it was originally used to describe forced labor used within the two groups pre-genocide. So, the country quite literally took the dark phrase and through discussion, awareness, and process, turned it into the community-building cleanup and service projects that it is today.

Finally, the most outstanding reflection of Rwanda’s profound rebirth is its Genocide Memorial, a burial ground for more than 250,000 genocide victims and a true site of healing. I personally had the privilege of visiting in 2017. I was completely enthralled by the peace and reckoning it holds. And yet, it was here, standing on the oasis-like grounds, when I looked down at my phone that had just buzzed with the CNN notification, “Charlottesville White Supremacy Rally Turns Deadly.” The quick notification informed me that there had been a series of hate crimes, counter-protests, and violence that led to a white supremacist neo-Nazi driving his car through a group of people.

So yes, refer to Rwanda as a third world country if you please. But, how on Earth was I standing in this so-called third world country, in which they so powerfully healed, discussed, and grew with their past when my own country was still experiencing three hundred ongoing years of terrorism and racism?

Owen Wright, 1877. Mary Dean, 1895. Wes Johnson, 1937. Breonna Taylor, 2020. George Floyd, 2020. Ahmaud Arbery, 2020, all names of Black Americans who have been brutally killed. America has been slaughtering for hundreds of years, not hundreds of days. According to the Equal Justice Initiative, “More than 4400 African American men, women, and children were hanged, burned alive, shot, drowned, and beaten to death by white mobs between 1877 and 1950.” And this number has only grown. We, Americans, can take a look at our countrymen and see that some continue to harm, terrorize, and kill. The same terrorism continues on from the first person enslaved, to the first person who was lynched, and to a system that so distinctly criminalizes and tortures Black Americans. A serious bloody wound sits as a serious scar on our country.

And for these reasons, because the wound keeps getting bigger and bloodier, we must powerfully empathize with those we’ve hurt, acknowledge our dark legacy, and actively pursue justice for those we continually discriminate against, just as Rwanda did. Bryan Stevenson, lawyer and founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, is leading our country in voicing the need for reconciling with the past, condemning inequality, and reconstructing a better society. He beautifully states, “We don’t like to talk about our history. And because of that, we really haven’t understood what it’s meant to do the things we’ve done historically… We have a hard time talking about race, and I believe it’s because we are unwilling to commit ourselves to a process of truth and reconciliation.” True healing and growth will not happen unless individuals and we as a society can face our past and recognize our positioning. As a white Gen-Z female, I need to be aware of my positionality and others’, and I need to actively pursue community healing and empathy.

So, maybe it was the fact that the term “third world country” was putting ranking on groups of people that bothered me. Or, maybe it bothered me because, in reality, this third world country should be our blueprint for reconciling with our ongoing racial inequality and terrorism in America. Let’s learn from Rwanda and one another and face our country’s sins together.

Piper Lyons | Nov 17, 2020 at 12:25 pm

This is amazing. I think you did a fantastic job analyzing how Rwanda and America have dealt with the worst parts of their history and I found it so interesting how the country that tends to be portrayed as lesser, is actually what we should be using as inspiration for how to deal with the problems in our own country. I feel like there are so many things for us as Americans to learn from other countries, yet we close ourselves off from it because “we are better than them.”

Annaita Gandhy | Nov 16, 2020 at 5:27 pm

Beautifully written! Thank you for this wise, sensitive and timely article.

Warren Bischoff | Nov 15, 2020 at 6:26 am

Hard to read with tears in my eyes, thanks for taking me back in time to Rwanda , an example for the world.

You really contrast the historical sins and stigmas of the USA with Rwanda, a place we look down upon, showing our ignorance.

Maybe your Gen Z crowd can make real changes.

Young women like you give me hope.

Thank you for this, profound. WB

Jeff Bischoff | Nov 14, 2020 at 11:58 am

Very well composed and presented message. Your research and stats and quotes, bolstered by your first hand experience made for an enjoyable read despite such an uncomfortable topic. Thanks for your perspectives, I learned some things.

Jeff Bischoff.